The behavior of feral hogs (also called wild hogs and wild pigs; Sus scrofa) is unique among native and introduced hoofed big game in the United States. Management strategies developed for other hoofed big game typically will not work successfully for feral hogs. Feral hogs are very intelligent, secretive, and adaptable. Feral hogs are capable of exploiting a wide variety of geographic locations, habitats and forage resources. Researchers observe that feral hogs are more difficult to study than other hoofed animals because of their “intelligence, shyness and vigilance combined with an acute sense of smell and hearing” (insert source).

Social Behavior

Feral hogs are social animals typically found in groups of two or more individuals, particularly females. The basic social unit is the sow and her litter, while mature males tend to be mostly solitary. These social units can be categorized into eleven groupings: single adults, adult groups, single subadults, subadult groups, groups of both adults and subadults, basic family groups (one adult with piglets), “sounders” (several adults with piglets), extended family groups (adults with both piglets and subadults), single piglets, piglet groups, and subadult and piglets groups. Depending upon the gender and age of an animal, an individual may temporarily occupy any one of eleven groupings. Group sizes vary greatly among populations from 2 to 30 or more individuals. Sounders are organized around two or three reproductively mature highly-related females and their litters, and can contain up to three generations of related animals, including subadults from previous litters. Very large groups of one hundred or more individuals do occur, and are normally observed in situations of a concentrated attractant, for example food resources such as agricultural crops, waterholes in arid areas or during dry seasons. These oversized groups are usually only a temporary localized phenomena and do not persist beyond the immediate site of the attraction.

Movements

Feral hogs occupy and exploit a wide variety of habitats. Feral hogs require reliable and adequate seasonally-available forage resources (for example, mast production during the fall and winter months) and daily access to well‑distributed water, shade and escape cover on a year-round basis. Feral hogs can thrive in a variety of ecoregions, including plains, mountains, humid swamps, and dry uplands. They live in remote areas and densely populated areas close to human civilization. They inhabit elevations from sea level up to 13,000 ft above msl. However, these animals do not tend to inhabit deserts, high mountain areas with substantial winter snowfall, or intensive agricultural areas where cover is scarce. Throughout its range, the feral hogs have shown a preference for riparian and wetland habitats. In addition, feral hogs will readily adjust to habitat changes caused by fire, logging, and natural catastrophes, except those that result in a loss of mast. Extreme flooding and heavy snowfalls can also cause these animals to move either up or down in elevation in an area to find suitable habitat.

The daily activity patterns of feral hogs vary by location. Because man nearly always and everywhere exercises influence on feral hog populations, it is difficult to regard them as either diurnal or nocturnal. In relatively undisturbed areas, feral hogs have been reported to trend toward diurnal activity. However, intense hunting pressure or human activity during the day will drive hogs to become more nocturnal. Feral hog activity patterns can also be seasonally driven. For example, feral hogs are generally reported to be diurnal during the fall, winter and spring months, with activity peaks in early morning and late afternoon and a reduction at midday. During the summer months, the diurnal activity is reduced and nocturnal activity is increased. The daily activity patterns also vary between the sexes. Sows maintain a relatively constant activity for prolonged periods, while boars exhibit brief bursts of movement followed by a lengthily periods of relative inactivity.

The movements of feral hogs appear to be characteristic of general wandering or drifting, but are restricted to a defined area or “home range” over extended periods of time. This wandering or drifting type of movement behavior is probably in response to the following: food availability, population density, reproductive activity, quality and interspersion of habitat, season, climatic conditions, disturbance by humans and social organization. For example, during poor mast years, feral hogs can become very nomadic in their search for alternative forage resources. Boars are consistently more mobile than sows on a daily basis. Intensive and prolonged disturbances (e.g., large-scale shooting or dogging control efforts) can cause these animals to permanently move to more remote locations several miles away.

Locomotion in feral hogs follows the standard gaits (that is, patterns of footfalls) seen in other large hoofed mammals including walking, trotting and galloping. In addition, the faster non-walking gaits visually include a “bouncing” trot, a “rocking” lope and a “steady/flat” flex-extension gallop or run. Feral hogs normally travel at a rate of 1-3 miles per hour; however, these animals are sure-footed, rapid runners and can travel relatively fast over open ground, reaching speeds of up to 20-30 miles per hour. In addition to being quick-footed on the ground, larger feral hogs can also physically jump over barriers as high as 3 feet. These animals are also very good, strong swimmers, being able to cross medium- to large-sized rivers and channels, as well as open waters up to 4 miles across.

Feral hogs exhibit a home range behavior, in that the movements of these animals are generally restricted to a defined area over an extended period of time. In general, feral hogs show a trend toward sedentary habits; however, depending upon ecological conditions, these animals may roam about widely in search of better forage conditions. Home range size in feral hogs is variable and averages about 6 mi2. The home range size is determined by a mixture of factors including the absolute and spatial availability of food, water and escape cover, the animal’s body weight, and the local density of hogs. For example, arid areas with poor food supplies have notably larger home ranges. Feral hog home ranges typically increase in size from daily to seasonal, and then to the cumulative annual area used. Boars have larger home ranges than sows. Further, some studies have shown that sows will reduce their home range just prior to giving birth and when their litters are being nursed.

Interactions and Aggression

Feral boars can be very aggressive toward one another. This intrasexual aggression among boars increases with age. Such interactions are typically, but not always, between two individual boars. The causes of this type of male-male fighting are primarily one of two things: typically, it is males competing for breeding opportunities with females; less often it can be competition for forage resources. Such fighting between boars can be intense, with either or both combatants getting injured, or possible even killed.

The behavior of mature sows in farrowing and caring for their young parallels that of their domestic counterparts. This encompasses a spectrum of maternal behavior from pre-parturition nest building through to the weaning of the litter. Pregnant sows build farrowing nests (Fig. 1) within 24 hours prior to giving birth to their litters. The primary function of this structure has been theorized as providing the newborn piglets with protection from inclement weather conditions. The birth of the piglets takes place in the nest. The young are typically born with the sow lying on her side, but can take place with the sow lying on her belly or even standing up. After being born, the piglets almost immediately begin to actively seek out the teats to begin suckling. The piglets do not follow the mother following birth, and will stay within or immediately around the farrowing nest for the first 1-2 weeks of life. During that time, the sow will make periodic but infrequent foraging trips away from the nest. Most of the time, the sow will stay in close physical contact with her litter to keep them warm, as well as near the nest to protect them from potential predators. Eventually, the family group will expand their foraging range progressively further away from the nest site. The sow will continue to lead and protect her litter through weaning and up until their dispersal away from the family group. The reported bravery exhibited by wild sows defending their young is legendary in anecdotal accounts, but is of questionable validity in reported observations made by field researchers.

Fig. 1. Appearance of a feral hog farrowing nest. Photo courtesy of Jack Mayer.

In order to protect themselves during periods of extended rest, feral hogs establish and use sheltered bedding areas. This usually entails the construction of loafing or resting beds. These structures are similar to but are less complex than farrowing nests. Loafing or resting beds can be used more than once, with some individuals returning to use a specific bed repeated times.

An individual feral hog’s mood or momentary temperament can generally be determined by their physical posture or body language at any particular time. The different mannerisms and postures described for these animals include an aggressive posture, a threatening charge, a submissive posture, a curiosity or alert posture, and play among juvenile animals.

The group size in feral hogs has an influence on the visual scanning that these animals do to detect the presence of predators. The scanning done by individual animals decreases with the increase of the group size. This behavior was also markedly different between solitary hogs and groups of any size, with the solitary animals doing significantly more visual scanning.

Vocalizations

A number of vocalizations have been identified for feral hogs, which include loud woofs or grunts, squeals, roars or growls, general contact grunting, low grunts, nursing grunts, feeding solicitation grunts, and teeth clacking or popping. Females and piglets of both sexes typically vocalize more often than do mature males.

Wallowing

Feral hogs wallow in order to lower body temperature and as a protective measure against insects (Fig. 2). Mud wallows are used by these animals year-round, with no seasonality of general use. However, wallows are used most frequently during the summer months when these sites are important to animals trying to behaviorally reduce their heat load. In addition, feral hogs will even break ice to use wallows during the winter. Mud wallows are used by both sexes and all age classes. However, wallowing may have a territorial function among boars during the peak of breeding.

Because these animals cannot cool themselves physiologically, feral hogs wallow throughout the year, especially during hot weather. Wallowing can contaminate water holes and negatively alter stream habitats. Wallowing is often found in conjunction with rooting activity (see Rooting). Wallowing, which is almost always combined with rooting, can affect ponds by muddying waters, creating algae blooms, creating bank erosion, destroying aquatic vegetation, and decreasing livestock use and fish production.

Fig. 2. Feral hog using a mud wallow. Photo courtesy of Jack Mayer.

Rubbing

Feral hogs frequently rub up against both natural and manmade objects (Fig. 3). The function of this behavior is to provide comfort, remove excess mud, remove hair and mechanically rid the body of external parasites (for example, hog lice and ticks). Rubs can involve almost any upright sturdy object, including trees (both pines and hardwoods), telephone poles, fence and sign posts, rocks and boulders, and various manmade things (for example, walls, buildings and parked vehicles). In most cases there is an association between rubs and mud wallows, such that if a wallow exists, rubs will also be present in the immediate vicinity.

Fig. 3. A telephone pole repeatedly rubbed by feral hogs. Photo courtesy of Jack Mayer.

Grooming

Several species of birds have been reported to physically forage on or groom feral hogs for external parasites. These have variously included Florida scrub jays (Aphelocoma coerulescens), common crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), and black-billed magpies (Pica pica). This behavior has involved the feral hogs being grooming while either standing or lying down. In some instances, the standing feral hogs were moving about foraging with the birds “riding” on their backs. Some hogs even appeared to solicit such grooming, by walking over to the birds in question and then lying down on their sides and waiting for the birds to begin grooming. This symbiotic behavior has reportedly involved both immature and mature feral hogs.

Scent Glands

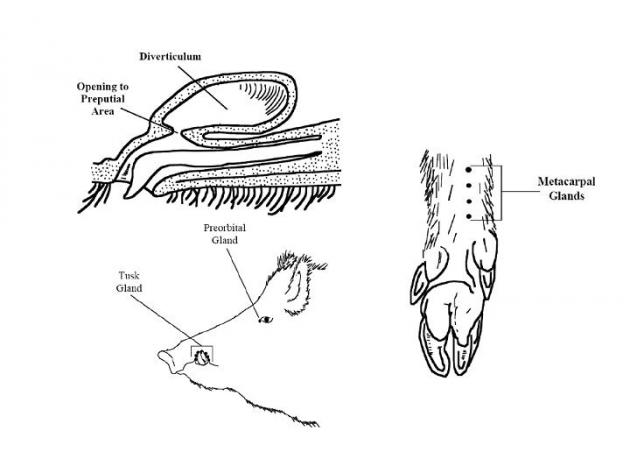

Feral hogs have and use a number of types of scent glands. The primary types of scent glands used by these animals include metacarpal glands, preorbital glands, preputial gland, and tusk glands (Figs. 4 and 5). Feral hogs also have proctoideal glands, perineal glands, mandibular or mental glands, and rhinarial glands. All of these secrete or produce odorous compounds, which may or may not function in scent marking.

Fig. 4. Illustrations showing the four most commonly used scent glands in feral hogs including the preputial gland or diverticulum (top left), metacarpal glands (right), preorbital gland (bottom left), and tusk gland (bottom left).

Fig. 5. Feral boar scent-marking with its metacarpal glands. Photo courtesy of Jack Mayer.

Five Senses

Of the five primary senses, feral hogs tend to use four of these (that is, smell, sight, hearing and touch) in their daily existence. Of these, feral hogs excel at the sense of smell. Few other animals have as well evolved and refined a sense of smell as do swine. Feral hogs are credited anecdotally with good, but not great eyesight. Hearing seems to be the least developed of the senses among these animals. Sense of touch within feral hogs is centered around the mouth. Not having manual dexterity in the form of a fingered hand, feral hogs use their mouth to “touch” or “pick up and feel” objects. Investigatory bites or chewing is not uncommon when hogs are presented with an object that is unknown to them.

Written by http://people.extension.org/drsus“>Jack Mayer.